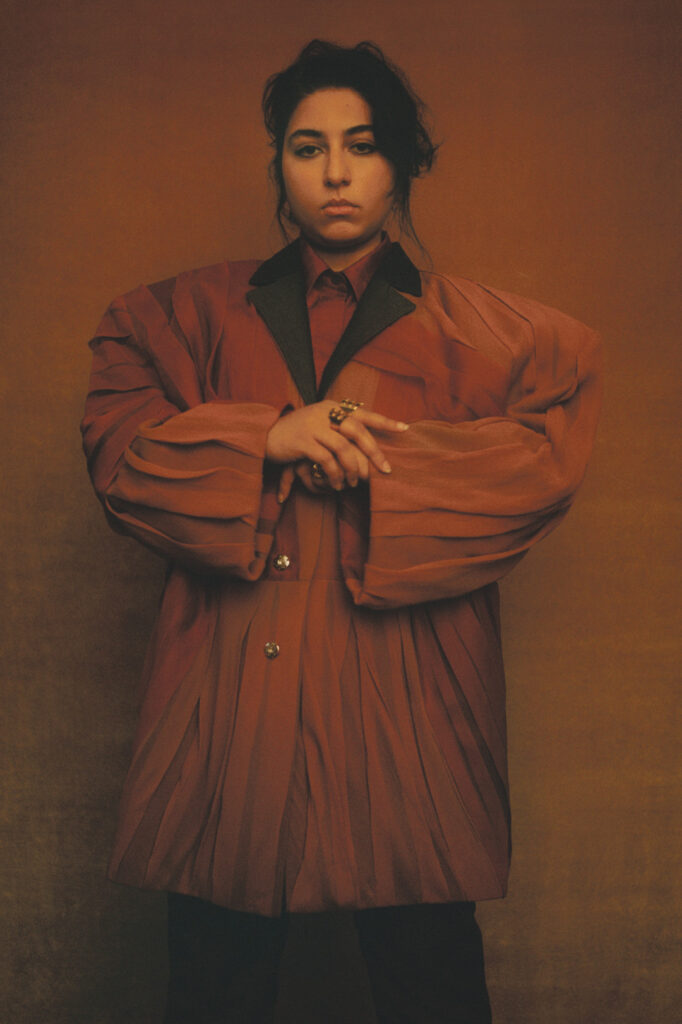

[vc_toggle title=”Lyrics: Mohabbat”] Mohabbat karne waale kam na hoñge Mohabbat karne waale kam na hoñge Terī mehfil meñ lekin ham na hoñge Zamāne bhar ke ġham yā ek terā ġham Zamāne bhar ke ġham yā ek terā ġham Ye ġham hogā to kitne ġham na hoñge Terī mehfil meñ lekin ham na hoñge Agar tū ittifāqan mil bhī jaa.e Agar tū ittifāqan mil bhī jaa.e Terī furqat ke sadme kam na hoñge Terī mehfil meñ lekin ham na hoñge Mohabbat karne waale kam na hoñge Mohabbat karne waalе kam na hoñge Terī mehfil mеñ ham na hoñge [/vc_toggle][vc_toggle title=”Tracklist: Vulture Prince”] 01. “Baghon Main” 02. “Diya Hai” 03. “Inayaat” 04. “Last Night” 05. “Mohabbat” 06. “Saans Lo“ 07. “Suroor“ [/vc_toggle]Arooj Aftab

Album: Vulture Prince

Release Date: 2021

USA

Known for her rapturous performances, Pakistani singer Abida Parveen is one of the most revered musicians in South Asian history. The 67-year-old is often referred to as the Queen of Sufi Music, a form of devotional Muslim poetry and song that pursues enlightenment via a deep, mystical relationship with God. So it takes a lot of guts to knock on Parveen’s door uninvited and proceed to partake in an impromptu singing session with her. In 2010, Arooj Aftab did just that.

Both musicians were scheduled to play the Sufi Music Festival in New York when Aftab tracked down Parveen’s hotel room number and made her move. Parveen recognized the then-25-year-old musician from a festival audition, welcomed her by grabbing her hand and giving her cookies, and eventually pulled out a harmonium so they could sing together. At one point, Aftab, who had just moved to New York City and was trying to find her footing, asked her hero, “What should I do with my life?” Parveen responded, “Listen to my albums.” [More on Pitchfork]

Your music has been getting a lot of global recognition but we don’t know much about yourself. Will you please tell us about yourself a little?

I was born in Saudi Arabia into a very musical family. I guess my parents just were really like, music was just part of the fabric of the whole situation and it was just live, coming through some of their friends and them singing themselves and then kind of also like listening to a lot of it and we were just like, elementally submerged in music throughout my childhood. We moved to Lahore when I was 11. I went to school there, I went to high school or we call it O levels and A levels. Throughout my teen years, I was just listening to a lot of music. I’m just sort of following the wave.

Lahore is a city of extreme. It’s a city that has so much history and poetry and dance and music. It’s just undeniably cultural architectural beauty: City of Gardens- they call it as well. It’s a very inspiring place to grow up as a teen. Just because there’s just so much environmental beauty around and the culture is so soaked in all this, like poetic nuance and stuff. So it was wonderful to kind of be in that for at least 10 years of my life. I just continued listening to a lot of different types of music and studying finance and stuff which didn’t really make sense. But hey, I mean, I liked math which has benefited me in my career because audio engineering is a lot of math and physics, and music is at many times math.

I just spent my time growing up having a very creative mind and also very connected to music. And then when I was done with high school I was looking for colleges and I really just ended up deciding that I wanted to study music and it was the one thing that I felt good about. At that young age, I just decided to commit to it.

And I believed in myself somehow for some reason, like, very much at an early stage when people really considered music to be a hobby. But, you know, there’s enough of us who have proven that it can become a full-on career and you can be very successful through it. So, yeah, I took out a massive student loan and I went to Berkeley.

I did music production engineering, jazz theory which I remember very little of (just kidding), and then voice and a little bit of film scoring. Then I moved to New York and I’ve been here since 2009. This is where I consider my home. I’ve just been here and kind of inheriting the multiverse that is New York in terms of cultures and people and the energies that come and go through, like, one of the world’s most metropolitan cities. And yeah, here we are.

One of the most powerful parts of your music is your poetic lyrics. Growing up listening to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan as a die-hard follower for years, I was soon going to realize that Urdu was so difficult to translate. How do you achieve to create your very own world while using such a sophisticated language? Especially for international listeners.

The poetry means a lot to me because I do understand it and it’s also just something that takes a while.

There’s a difference between understanding lyrics or understanding a language and really making the poetry in that language your own. And that does definitely take a while because words and someone else’s story can just mean nothing until you make it relevant to yourself and you internalize those words in that poetry, especially if you’re going to sing it, you have to really sing it as if it’s really coming from you.

So it doesn’t feel extremely borrowed or just like you’re doing a cover or whatever. Musically, I think that my skills as an arranger and a producer and as someone who knows how to fuck with sound and the sound of instruments and how they go together, how different instruments blend together, and just the imagination of what the realm can be with these instruments.

Like, I think that has developed quite a bit over time because I just think about it all the time. I think about it more than the poetry or the singing. I think about the realm of sound and how I’m going to curate that to make it feel like we’re somewhere and we’re nowhere and it’s very new and it’s not, so it can remind you of multiple things at the same time.

It can take on a life of its own. There can be many different sections of the song that all kind of go together. But it’s almost as if you’re walking and a door opens and then you’re in another space from the beginning of the song to the end. I’ve just been kind of thinking about that as a focus point of where I want my musicianship to grow next these last few years.

And so, I think creating one’s own world while using this language comes from sort of being aware of all those things.

With full respect, I genuinely think Master Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music would sound just like yours if he happened to live in our times as a Brooklyner, like, yourself. How do you think coming to the US affected your art?

I think I would disagree with that because it sounds like you’re saying that this music can only like the music that like, it would sound like mine if he lived in Brooklyn. maybe I’m interpreting this wrongly, but it sounds like you’re saying that this, that my music sounds like the way that it does because, because it’s attributed to being here in the West.

I think that like the amount of sort of intentional learning and like sort of, you know, music is accessible globally. It’s not something that is isolated, it’s not something that only lives in one part of the world. and especially music, musical creativity and, and innovation can happen really anywhere. And it mostly happens in people’s minds.

And of course, it happens because they’re expanding their minds by like listening to a lot of different types of music and meeting a lot of different types of people and kind of investigating a lot of different types of experiences and cultures and inheriting those and spending a lot of time and energy really just inheriting those. and spending a lot of time and energy, really actively trying to create something that is new, which I think kind of has always been the case with me

even from before, I was in the US. So I think there’s one way that like a very classical person like Nusra would maybe collaborate with someone like a producer and then kind of arrive at a style that would be different from the, from their classical traditional way. But I also think it’s important to realize that sometimes classical musicians don’t necessarily want to remove themselves from the class classical realm.

They want to stay there. They are very purist in that, in that regard. And sometimes the classical musician doesn’t need to collaborate or relocate. They themselves are interested in developing you know, an alternative sound. So, you know, it it’s, it’s really a much bigger, it’s much, it’s, it’s a much bigger explanation than just like, because you move to the US, this is what’s happening.

You know, it’s like that.

Do you receive negative criticism of your music from back home? What kind of feedback do you get from different Pakistani generations?

Again, yeah, like, there’s definitely just been a lot of overwhelming positive feedback always. And there are people who don’t like change. There are people who really are purists and they don’t like innovation, and that’s just what they like. So there’s really nothing we can do about that. But for the most part, the response has been quite overwhelmingly positive.

Based in Brooklyn, how do you manage to preserve your relationship with Urdu and ghazals? Do you have any social projects in mind that are based on Urdu?

I have Pakistani friends who live in Brooklyn, who live all over the world and who live in Pakistan and we’re in constant kind of contact with each other and some of them are quite poetically inclined and some of them are not. So it’s just kind of like a mix. Just because I’m based here, doesn’t mean that I am completely cut off from having access to that cultural history of my life. But I mean, it is hard because you’re not fully submerged in it and I’m not like there in libraries looking for stuff, but also everybody inherits inspiration differently. But I think that, for me it’s more about talking to my brother or my dad or my friends and just kind of watching music videos on YouTube from like the 70s and exploring stuff in that way. I think you have to really be dedicated to, preserving that relationship and you have to be creative about how you’ll preserve it and what steps you need to take. And, of course, when you’re living abroad, it affects the easiness of that but there’s a lot out there. You know, it’s not terrible, it’s not that terribly hard.

Do I have any special projects in mind that are based on Urdu, or the culture? Oh, yeah. I don’t know if they’ll come to fruition but I do have some things in the pipeline!

What are the main subjects you talk about in your songs, especially in your new album, Vulture Prince?

In my first album, it was mostly about departure and like the sense of missing someone and sort of not understanding the fact that love can end or people move on. It was more about love and the connection- the higher connections that love can create. And it was basically about departure of a lover and waiting for them to come back.

And then Vulture Prince has been very much about, I would just say, kind of like coming to terms with the fact that the world is very disappointing. And that there’s nothing really you can do about it and that you have to be more positive and hopeful. It’s less about love and more about life. It’s a little bit more mature than just heartbreak and literally just love relationships. It’s about your relationship with the world, your relationship with your family, your relationship with places. And how they change and how the ebb and flow and the kind of developing fucking thing that happens. Like, I mean, how everything is just kind of moving forward and sometimes you feel a little left behind or sometimes you feel like you just can’t take a break to actually process things because you have to keep going because the world is just relentlessly continuously turning.

I don’t want to go in detail but you have gone through a lot in your personal life during the making of your album. What does Vulture Prince mean to you personally?

I think Vulture Prince for me personally has been an emotional aid. I’ve always used music to heal myself and get through rough times.

And it’s kind of like my lifeline, it always has been and I feel like it is that way for a lot of musicians. And so once again, it’s like my best friend that doesn’t really ever disappoint me. So, I think Vulture Prince means a lot of healing to me and the healing isn’t really over, you know.

It feels like it’s emotionally something that carries me forward into the next moment. But at the same time, it’s also one of my proudest musical moments where a lot of things for me technically and musically specifically came together so kind of combining both of those things. That’s what Vulture Prince does mean to me.

We have been running a loop-songs series and I love love love it especially when we host a non-English song. Our pick is your incredible song, Mohabbat. Before we talk about the song, I would love to ask you about the word ‘mohabbat’ itself. Having Turkish origins myself, it is one of those words that will not translate 100%. What kind of ‘love’ is described when you say mohabbat? Will you please enlighten our readers about etymology?

When I say mohabbat, it’s like there’s conversations that happen between me and my friends and other people that I’m close to who advise me about music and culture. And, you know, it’s like, it’s not just love, it’s not just desire, it’s not just affection. It’s like, it’s one of these these multifaceted words that don’t really have a clear explanation in English.

And it can take on so many forms and it takes on a lot of different forms in the song itself, as well. Like just saying, you have so many people who love you, but I won’t be one of them. It’s definitely like not saying that literally, right? It’s like so many people who love being the word, but it’s like you have so many people who love you. But it also is saying there so many people who are obsessed with you, like, it could be yes men.

It could be. You know, someone who is maybe a saint and has a lot of followers and like someone is saying, but I’m not going to be one of your followers anymore. You know, the ideas. The possibilities are just endless of what this word could allude to based on how you’re feeling even that day. So I think it’s fantastic and one should keep exploring what it could mean.

How about your dreamy journey, Mohabbat? What is the back story of the song if you can go a bit deeper for us? And what is the significance of it for you and the album?

Yeah, it’s just such a chameleon of a song lyrically. It just kind of reminds me of so many scenarios that I could possibly relate it to, you know, like I said earlier, could be a worshiper is kind of deciding not to follow that, that, that I don’t know deity anymore or it could be that like a lover is tired of, you know, is kind of mocking their, their ex and saying, you know, what, like you’re gonna, there’s many fish in the sea for you like you’re, you’re gonna be fine. I’m, but I’m, I’m, I’m leaving you, you know, or it could be that someone, someone has passed away and is saying, you know, don’t worry, I’m gonna go, but you’ll still find love, you’ll still be OK, like, it can be so many things and I feel like that’s really beautiful and that’s kind of what has always resonated with me about this particular guzzle. But I felt in this case particularly that, like, I wanted to do more, I just didn’t want to do this. I just didn’t want it to be focused on the poetry, which is, which already is so incredible, but I wanted to really like add and like, like 100% of myself into it as well musically. And that’s kind of how the, it almost like I approached it almost like it has movements, you know, it has like the first movement and the second and then the kind of percussive part and then this this kind of you know, synth interlude that’s kind of cold and then becomes a little jarring. And then, you know, towards the end, there are these like shimmers of horn and, you know, the final kind of wrap up of the, of the story. So even if you don’t really understand what’s happening lyrically, you are kind of completely immersed in the story that the music is telling you and is leading you, is leading you on.

So that’s kind of where I wanted it to be like my crown jewel of this, of the album. And I was really nervous that it was that I was doing too much and that it was all in my head, but I’m very, very happy and grateful that it did come out and people are feeling it the way that I intended for them to feel it. At least, like, at least some people are, you know, we can only, we can only dream and, and, and, and kind of go completely like, artistically bonkers and just like, you know, musicians can when they’re, when they’re in this way where they’re trying to sort of realize something out of thin air, you can just feel like you’re completely insane. And like, you have to kind of enter a level of self importance that’s just very like embarrassing for the rest of the world, but you just have to fucking behave like that until you really get it.

When we interview bands on their songs, I occasionally ask if they’ll be making a video for the song. When it comes to Mohabbat (and your music in general) though, just as the difficulty level of Urdu ghazals, it feels like it would be a hard task to wrap up that musical journey with images. I mean, it feels like everybody will get their own share from the tune itself- like a shelter for everyone. How have you reached this consciousness level so young and what should we expect from you for the future?

I don’t know how I’ve reached this consciousness level so young. I mean that’s a very generous way to put it. It is hard for me to imagine what the videos would look like, which is why, I mean, I’m sure you’ve noticed that there are no videos of for any of my music or maybe there’s one or two that are kind of focused on a dancer and less about me, I’m not even in the video. They’re more like live, a video of us playing the song, live a conceptual video or any kind.

Yeah, like it’s still something that I am not. I haven’t, this is why, you know, it’s not on me to figure this out. I mean, I guess it is a little bit but I really have to work with like an incredible music video director or someone who can kind of hear out my ramblings and like make sense of it and create some really stunning visual accompaniment to this music because I’m kind of like, that’s really, I don’t think my forte and it doesn’t have to be.

So I am hoping, I think again, like from the business aspect of it, from the professional aspect of it, you can’t really be an up and coming artist without really having any visual content. Unfortunately, like we’re still kind of in that model, although I hope it changes soon. But yeah, I think that in the future, there’s definitely going to be more visual assets that accompany the album.

But for now, I haven’t really met someone who could do that yet for me yet or like collaborate on that level. Anyway, I have to run, I have a meeting, but I’m gonna send this to you guys now and I hope you can make sense of it and please don’t make me sound like an idiot. And thank you once again for the wonderful questions. And yeah, looking forward to the article.